Photo credit: Crawford Auto Aviation Collection at the Western Reserve Historical Society.

Photo credit: Crawford Auto Aviation Collection at the Western Reserve Historical Society.

Today, the winner is clear: Henry Ford in Detroit, Michigan. But, in the early days of automobile manufacturing, the answer wasn’t so obvious – and, in fact, Alexander Winton and Cleveland, Ohio as the Motor City had the early edge.

A step back in time

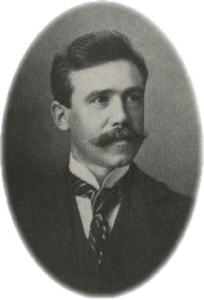

In March 1897, Scottish immigrant Alexander Winton incorporated Winton Motor Car Company in Cleveland. In May 1897, Winton’s vehicle surged to new heights as it traveled 33.64 miles per hour around a Cleveland horse track. Even after this dazzling demonstration of power, though, people still doubted the durability of the automobile and Winton needed to find a way to convince them.

Reliability Run #1

A showman at heart, Winton decided to tackle a significant challenge to draw attention to his vehicle. On July 28, 1897, Winton and an employee left Cleveland for New York City, traveling 700 miles to prove the reliability of his vehicle. He arrived safely on August 7, after 78 hours and 43 hours of driving time. He didn’t get as much attention as he’d wanted, which was disappointing, but he stayed focused and created four more custom-built motor cars.

On March 24, 1898, he sold one of his vehicles – which might not sound like a big deal, except it was the first “American-made standard-model gasoline automobile” ever sold. He sold it to Robert Allison of Port Carbon, Pennsylvania for the astonishing sum of $1,000 (nearly $28,000 today) after Allison saw a Winton ad in Scientific American. That year, more than 100 Wintons were sold, making his company the largest manufacturer of gas-powered automobiles in the nation.

Reliability Run #2

On May 22, 1899, Winton began a five-day trip to New York, this time with a journalist who’d worked for the Plain Dealer in Cleveland before fighting in the Spanish American War, a man named Charles Shanks. A newspaper article predicted that “the automobile will doubtless become the most convenient mode of transport during the 20th century. The Plain Dealer is endeavoring to demonstrate the entire feasibility of this mode of locomotion.”

This trip generated the publicity Winton craved and boosted sales, with Winton selling 21 more vehicles during the rest of 1899. As for Shanks, he coined the term “automobile” on this journey, which is his lasting legacy. Photo credit: Crawford Auto Aviation Collection at the Western Reserve Historical Society.

Photo credit: Crawford Auto Aviation Collection at the Western Reserve Historical Society.

Re-enactment: the 1997 Winton Centennial

In retrospect, it’s hard to imagine what a big adventure these Cleveland-to-New-York trips really were. But, to get somewhat of a sense, Advance Auto Parts talked to journalist Chris Jensen who, in 1997, participated in a re-enactment of the trip. At the time, Chris wrote for the Plain Dealer, the newspaper that sponsored the second reliability run in 1899. He recorded his 1997 adventures in that newspaper as he traveled to New York in an 1899 Winton.

Only three known 1899 Wintons exist today and Chris rode in one now belonging to the Frederick C. Crawford Auto Aviation Collection at the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland. The trip was reported in a series of articles in the Plain Dealer. He was the passenger in a vehicle driven by Charles “Charlie” F. Wake, one of Winton’s great-grandsons.

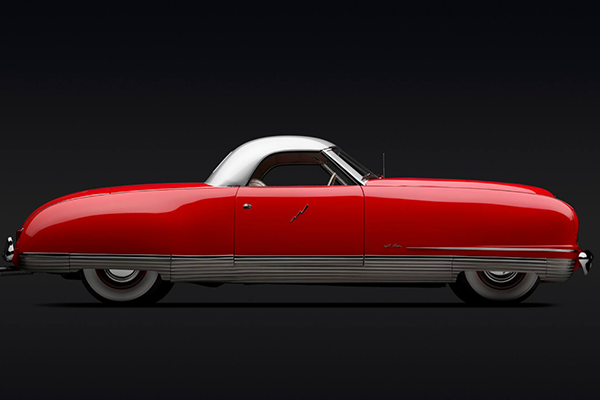

In the re-enactment, 13 other Wintons traveled alongside Chris’s vehicle, the newest being the 1922 model. “This showed how quickly automobiles evolved,” he says, “from the little putt-putt that we were in to Wintons that looked like real cars.”

The wheelbase of the 1899 Winton was only 69 inches, with an overall length of 104 inches. “That makes a Toyota Tercel,” Chris pointed out in an article, “with a 94-inch wheelbase and an overall length of 162 inches seem like a stretch limo.”

The vehicle boasted 8 horsepower and had a one-cylinder, 117-cubic-inch engine that was “banging away and it sounds like the world’s loudest smoker’s cough.”

During the trip, Chris and Charlie were perched up high on the tiny two-seater, on a tufted bench-like seat. Because the top of the vehicle didn’t offer any real protection, the men didn’t use it. “So, there was nothing between me and anything else, including the road,” Chris recalls. “When it rained, I got really, really wet.”

But, there was an upside. “Because we were going at a low speed,” Chris shares with Advance Auto parts, “at 15 to 20 miles per hour, I got to look closely at what was around me instead of zooming past. I got a new appreciation for the hills and how long it took to go both up and down.”

“Going downhill,” he adds, “was pretty interesting because there were basically no brakes. People have asked me, ‘If you were only going 15 miles per hour, what could go wrong?’ and the reality is that, with no real brakes and no seat belts, there is a lot that could go wrong. Picture yourself flying through the air at 15 to 20 miles per hour and crashing into a telephone pole.”

Fortunately, no such accidents happened during the re-enactment. “But,” Chris points out, “we traveled on good roads. Try to imagine people traveling along in mud and rocks and facing other challenges. Plus, the maps weren’t great and it wasn’t always clear, in the 1890s, where you were going. And, if they broke down, who was there to help with repairs?”

Any time the vehicle needed re-started, it needed cranked. “It took a fair amount of effort,” Chris says. “And, as you were driving, you needed to keep pouring oil into it, to keep the car moving along. The oil would drop out onto the ground as you went.” Where the oil was supposed to go: into three troughs that had tubes designed to drip the oil into the transmission, the engine and the differential. The steering happened via a tiller attached to the front wheels, a somewhat scary set-up. As for turning signals, brake lights and headlights, they didn’t exist.

Putting all into perspective

In spite of all of the modern devices that either didn’t yet exist or were sub-standard in the century vehicles from the 1890s and early 20th century, the Winton was the premiere choice of its day, the most powerful, the most technically advanced. Alexander Winton was king of the mountain, with Henry Ford someone whom Winton declined to hire in 1899 when given the chance.

In 1901, when several members of the wealthy Vanderbilt family chose to buy automobiles, they selected Winton vehicles. Winton, flush with his success, built a factory on the west side of Cleveland, at a time when most people building automobiles did so in their personal barns or garages.

Winton began competing in races, with his vehicles usually winning. In 1903, when Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson made the first-ever cross-country drive, he did so in a Winton. When Alice Ramsey became the first woman to drive cross country, she also chose a Winton.

A change is in the air

Although Wintons received praise, one early customer reportedly wasn’t impressed. When James Ward Packard complained about his new vehicle, Winton allegedly challenged him to do better, the result ultimately becoming the Packard automobile company.

Then there was the race of October 10, 1901.

Winton entered this race as the man to beat – with the automobile to beat. It’s unlikely that he worried too much about one of his competitors: Henry Ford. For the most part, Ford was known as the man who’d founded the floundering Detroit Automobile Company on August 5, 1899 – a company that failed on November 20, 1901 after building just 12 vehicles.

However, Winton’s automobile experienced mechanical difficulties at the 8-mile mark of this 10-mile race and Ford passed him up to win. After Ford’s win, people began ponying up for his next venture, the Henry Ford Company (founded on November 3, 1901, apparently in anticipation of the Detroit Automobile Company closing).

The next year, Winton was determined to beat Ford in a race. After all, the 1902 Winton Bullet reached speeds of 70 miles per hour, the unofficial land record. And, yet, Ford’s driver Barney Oldfield won the race – while Ford suffered another loss with the collapse of the Henry Ford Company on August 22, 1902. With funds in part raised from Oldfield’s win, Ford decided to finance a third automobile company: the Ford Motor Company.

Although Winton continued to build vehicles until 1924, his business slowly declined while Ford revolutionized manufacturing:

- In 1908, Ford came out with the affordable “Model T” or “Tin Lizzy” that made automobile buying possible for the middle class

- In the fall of 1913, Ford began operation of the world’s first moving assembly line for automobiles

- On January 5, 1914, Ford began paying his workers $5 per day, more than double the previous rate – and more than double what any other automobile company was paying. Job seekers flocked to become part of Ford Motor Company.

Derek E. Moore, the curator of transportation history at the Western Reserve Historical Society, points out that “Cleveland companies continued to manufacture higher quality automobiles, but they were higher priced and, so, a limited market. Therefore, fewer people bought from Cleveland than Detroit.”

As a point of comparison, in 1924:

- 2 million Fords were manufactured, with prices ranging from $295 ($4,041 in today’s dollars) to $685 ($9,384 in today’s dollars)

- Winton’s least expensive model cost $2,295 (comparable to $31,438); this is the last year of Winton’s automobile production and we know that, in 1922, he made only 690 vehicles

Interestingly enough, Derek says that Ford built his first assembly plant for the Model T, outside of Detroit, in Cleveland where the Cleveland Institute of Art is currently housed. “Ford would ship components to Cleveland, knowing that it was easier and cheaper to ship parts than fully built automobiles, and then the vehicles could be sold in the Cleveland area.”

You already know the rest of the story. Although Cleveland continued to play a significant role in automobile manufacturing and assembly, the title of Motor City ultimately went to Detroit, with its king named Henry Ford.