Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

Although it’s been a long time since you could purchase a brand new Studebaker, this brand once dominated the country, even before “horseless carriages” were available.

The Studebaker National Museum, located in South Bend, Indiana, contains more than 120 of these vehicles–meaning both cars and wagons–some dating back to the late 1880s. Typically, there are 70 vehicles or so on display at any one time. Vehicles include four presidential carriages, the first and last cars built in South Bend, the last Studebaker ever built, anywhere, and many other iconic vehicles.

But, the history of Studebaker begins more than twenty years before 1880. Here’s more.

History of Studebaker Company

Imagine yourself as a blacksmith in 1852. You decide to partner with your brother to open up a blacksmith shop, say, at the corner of Michigan and Jefferson Streets in South Bend, Indiana of February 16th of that year. You might expect to spend your days in front of an immensely hot forge filled with burning coals, putting bars of metal into the heat and then shaping them into axes or nails, or pots and pans, or door hinges or plow blades.

If you were Henry and Clement Studebaker, though, your business would develop a niche specialty, much like businesses do today, and it didn’t fit the typical blacksmithing mold. By the time their company morphed from H & C Studebaker into the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company, they were in fact the world’s largest manufacturer of farm wagons and horse-drawn buggies.

Henry and Clement began making metal parts for freight wagons in 1852, with start-up capital of only $68 (equal to slightly more than $2,000 of today’s dollars). Freight wagons were railway cars, non-powered, that transported cargo.

On their first day of business, they had exactly one customer–a man who needed a shoe changed on his horse. Later that year, though, they were able to charge a customer $175 (comparable to about $5,300 in 2014 dollars and more than twice as much as all of their startup funding) to build a farm wagon. They painted the wagon green and red and boldly added “Studebaker” in yellow lettering, the first time a vehicle boasted their name. Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

In 1853, Henry’s and Clement’s younger brother John Mohler decided to head out west to find gold, something countless men of his generation were doing. A wagon train would take him along without charging a fee as long as the brothers donated a wagon to the cause. The family agreed and, with $65 in his pocket, John sought out his fortune. Although he didn’t find the riches he desired, his talents as a wagon maker earned him regular work and allowed him to save up $8,000.

In Indiana, Henry and Clement continued their blacksmithing work, but also built about a dozen wagons per year. To get more into mass production, they needed more funds. Fortunately, John had those funds and, in 1858, he returned home, bought out Henry’s share in the business, and became part of the family business.

The previous year–1857–they’d also expanded their horizons by building and selling a carriage. According to A Century on Wheels: The Story of Studebaker, “Fancy, hand-worked iron trim, the kind of courting buggy any boy and girl would be proud to be seen in.” By 1860, their brother Peter Everst Studebaker was showing the family wares in Goshen, Indiana, the first of the Studebaker showrooms, albeit one that looked more like a shed. A fifth brother, Jacob Franklin, also ended up joining the company.

When the Civil War started, there was a huge need for wagons and so Clement, Peter and John shipped their wagons to the Union Army by train and steamship. In 1868, they formed the Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company, which ultimately became the “largest vehicle house in the world” despite two massive fires destroying their buildings. By 1877, annual sales exceeded $1 million and Clement traveled to Europe to find more markets for the company. The following year, their wagons won awards at the prestigious Paris Exposition.

They even sold a $20,000 version of their vehicle (figure $445,000 in today’s dollars, comparable to a Lamborghini Aventador), which could seat a dozen passengers. In the late 1880s, the family also bought out companies manufacturing the Lafayette and Lincoln carriages, further increasing their market share.

Era of the Horseless Carriage Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

In 1895, John’s son in law, Frederick Fish, began pushing for a horseless carriage to add to their product line. In 1897, Fred became the chairman of the executive committee and the company began actively working on an electric motor. Meanwhile, their wagon division continued to be strong as, in 1898, the company supplied wagons for the Spanish American War. Plus, the American Red Cross bought six yellow and blue ambulances and sent them to Cuba; each ambulance carried four stretchers, the bottom two hinged to be moved for sitting patients or medical personnel.

And, in 1902 the Studebakers debuted their first electric car. This was a year later than the Oldsmobile’s version and less complex than the Thomas B. Jeffrey Company’s 1902 entry of a gas-powered model, the Rambler. Thomas B. Jeffrey sold 1,500 Ramblers that years, compared to Studebaker’s 20 electric cars. More competition was right around the corner, too, thanks to Henry Ford, as well as the Overland, the precursor of the Jeep. Nevertheless, the purchaser of the second Studebaker electric car carried some real clout: a guy named Thomas Edison.

Although electric cars are certainly a 21st-century buzzword, there was a flaw in them in 1902: too many places simply didn’t have electricity, so where could you recharge your car? You certainly couldn’t lug along a can or two of emergency electricity like you could fuel, so electric car owners often saw their vehicles towed home by horses, which surely seemed a step back in technology.

The future, at least for the next century, was therefore a much smellier, less elegant option. Or as John “Wheelbarrow Johnny” Studebaker called gasoline-based cars, “clumsy, noisy, dangerous brutes stink to high heaven, break down at the worst possible moment and are a public nuisance.”

Birth of the gas-powered Studebaker Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

The company began making gasoline-powered cars in 1904 in partnership with the Garford Company of Elyria, Ohio, located near Cleveland. What a confusing job it must have been to market Studebakers in this era, when they still sold horse-drawn carriages for the traditionalists, electric cars for drivers willing to stick close to home and max out at about 13 miles an hour, and gasoline vehicles “for wide-radius touring.”

By 1908, Studebaker had bought a majority interest in the Garford Company, but their cars were expensive–$2,500 to $4,500, and sometimes even more–and fewer than 2,500 were likely built during the entire 8-year partnership. Moreover, in 1908, Ford introduced Model Ts that sold for only $825-850, manufacturing more than 10,000 in just one year.

The year 1911 saw the end of Studebaker electric vehicle production as well as the demise of the partnership with Garford, although various other collaborations were tried for the gas-powered models. In 1914, Studebaker started supplying Britain, France and Russia with wagons for World War I, the last major war that relied heavily upon wagons. Later, they also supplied the United States in their war effort.

In May 1920, the company stopped production of horse-drawn carriages, liquidating their product line while they could still get reasonable prices for the vehicles. All told, they lost more than $700,000 in this move, but losses surely would have been greater had they waited. Ready to cringe, though? That figure translates into more than an $8 million loss today.

From this point on, the Studebaker company would flourish–or stumble–based on automobiles alone. Highlights of the next couple of decades include:

- The company struggled during the Great Depression, as many others did, even going into receivership from 1933 through 1935.

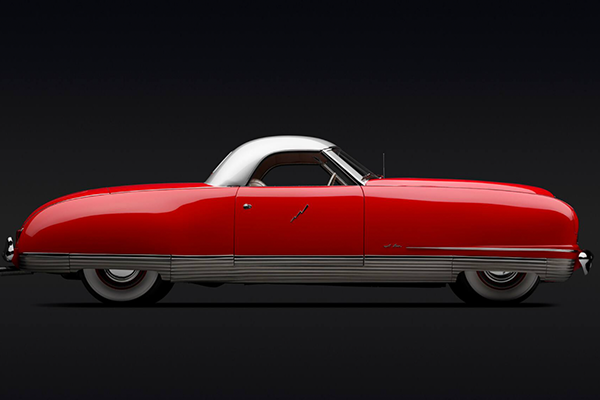

- The 1939 Champion is considered one of Studebaker’s most iconic cars.

- In 1939, the company began building a small quantity of 6 x 6 military trucks for the French forces in World War II. Later, they provided B-17 Flying Fortress engines and the M29 and M29C amphibious Weasel personnel carrier.

- After the war, Studebaker emerged with the first new design for a post-war car (production for personal cars halted in 1942 so that more efforts could be given to support the war).

- The 1947 Starlight Coupe is another of Studebaker’s most well-known vehicles.

- In 1948, production became multi-national once again with a production facility in Hamilton, Ontario in Canada. Studebaker had begun building cars in Canada in 1910, but stopped from 1936-1947.

- In 1950, the bullet nose design was introduced.

- The following year, the Studebaker V-8 was unveiled.

- The 1963 Avanti is considered one of Studebaker’s most iconic cars.

Also in 1963: more than 110 years after Henry and Clement first set up shop, the US production of Studebaker vehicles stopped. On March 17, 1966, the final Studebaker produced anywhere in the world rolled out in Canada.

Studebaker National Museum

Fortunately, the Studebaker National Museum has preserved a significant amount of the company’s history. “The museum,” says archivist Andrew Beckman, “began with 37 vehicles. We are one of only three car museums with the American Alliance of Museum accreditation, which is sort of the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval for museums.” The other two, he says, are the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan and the Auburn Cord Duesenberg in Auburn, Indiana. Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

He points out that the 1950 and 1951 Bullet Nose vehicles are among the car museum’s most popular for visitors. Other vehicles of interest include the presidential ones, which include:

- Ulysses S. Grant’s vehicle used during his presidential term from 1873 until 1877, which he continued to use until his death in 1885. Visitors who rode in this landau-style carriage included:

- President Rutherford B. Hayes

- President Chester A. Arthur

- Civil War General William T. Sherman

- Civil War General Phil Sheridan

- King Kalakua of the Hawaiian Islands

- Viceroy Li Hung Chang from the Chinese Empire

- One of Benjamin Harrison’s five carriages used during his presidential term; altogether, these carriages cost $7,075 and were considered less pretentious than other choices (in keeping with Harrison’s personality) because they were “simple in design with silver and ebony trimmings rather than fancier gilt, and they bore no formal insignias.” Harrison continued to buy Studebaker carriages until his death in 1901.

- Abraham Lincoln’s carriage that transported him (and his wife) to Ford Theater on the night of his assassination on April 15, 1865. This carriage has six springs, along with solid silver lamps, door handles and hubcaps. Because the steps connect to the doors, they lowered and rose as the doors opened and closed.

- William McKinley’s carriage, one that boasted rubber tires for summer use and a removable extension top, along with springs and cushions in the seats. Like Lincoln, McKinley traveled in this carriage on the day of his assassination in September 1901.

Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

Photo credit: Studebaker National Museum.

When asked why there is still such interest in Studebakers, nearly 50 years after production stopped, Beckman points out the longevity of the company. “This was the only company,” he says, “that successfully transitioned from the wagon business to the car business.” And, as author Patrick Foster points out in his book, Studebaker: The Complete History, “For many years, Studebaker held the proud claim as the vehicle owned by more Americans than any other brand. No mere local or regional phenomenon, Studebaker vehicles were known and respected around the world. An argument could be made that Studebaker was the first truly global vehicle brand. Studebaker was the natural choice of princes, kings and presidents.”

As proof of the continuing fascination with the Studebaker, Beckman shares that, even on the date of this interview, the blizzard of March 12, 2014, people figured out a way to get to the museum to see a presentation about the vehicle. Overall, approximately 40,000 people visit the museum each year, although the number increases once every five years when the international Studebaker meet takes place in South Bend. The museum has also witnessed an increase in moms with strollers, ever since they added an interactive children’s exhibit area about one and a half years ago. People also actively participate in Studebaker car clubs. In fact, Beckman says, “it’s the largest single mark auto club in existence.”

Editor's note: Have you been to this car museum? If so, what did you think? If not, which car museums would you like to visit? And, be sure to let us know what your favorite vintage cars are.