"It is indeed a queer thing...that while the motor industry is one of the most powerful in the country, no important courses are being given in the schools in automobile design. Such a course should depend upon the closest cooperation between the students and the automobile industry." — Harley Earl, 1920

Source | Richard Earl

When people think of the early days of the automotive industry, they tend to think of Ford's utilitarian Model T, which Henry Ford famously said was available in any color "as long as it was black." There's no question that Ford's philosophy and production methods revolutionized the industrial world with the simple and affordable Model T, but it wasn't long before drivers wanted some variety and personality in their vehicles.

In those days, no automaker had anything like a design department. Cars were designed to be utilitarian machines with no more style or identity than a hay baler or a drill press. But as the market for cars grew, so did the opportunity for creative automotive design. Enter Harley J. Earl. Joining GM in 1930, Earl and his design department found a place at the table and had a voice in the company's direction.

Factors like styling, model differences, options and color were soon to give GM the edge in engineering as well as marketing and sales. Seen through that prism, it's not an overstatement to say that HJE was singlehandedly responsible for developing the number-one reason for automotive sales for the next eight or ten decades to come.

Earl saw industrial design and the nuts-and-bolts of engineering as being joined at the hip, inseparable from each other. It's this approach that made him a true pioneer, as he was as much an artist as an engineer, and saw the two disciplines through the same lens.

Harley Earl is far from being a household name, since he wasn't insistent on taking credit for every last thing he did and enjoyed being anonymous in his work. The innovations he introduced at GM soon became industry standards, and the philosophy he brought did more than just translate into products—it irreversibly changed the direction of American pop culture in the 20th century.

Art and Color Section

Suddenly, how cars looked mattered as much as how they were designed, or how they performed. It mattered enough for GM to establish the Art and Color Section (now known as the Design and Styling Department) in 1927, and left other manufacturers playing catch-up when it came to design.

According to designer Homer LaGassey, “Harley was the first to hire Left Bank artists and tell them to put on a tie and come and work for me inside General Motors."

The first step in design and styling was to work up sketches, many of which were developed by Earl himself. Earl's grandson Richard Earl was kind enough to share some of these exciting sketches for 1950s and 60s GM designs. From these sketches you can really see how the designer's imagination played out:

With styling playing a bigger role, it was necessary for designers to find ways to realize their ideas and take them from sketches to 3D, and that's when the clay model process was developed. Like a sculptor working with stone or clay, designers could now present designs in ways that sketches, reports and diagrams could never communicate. Teams could work together and make changes, adding a little detail here or removing a little excess there, smoothing lines and carving contours. The beauty of clay (actually a material called industrial plasticene) was the collaborative nature of the process and the fact that it could be changed and altered as needed.

The clay would be applied over an armature or framework that had roughly the same dimensions as the final product. After this scale models (roughly 4:10 scale) were developed. Here's a fascinating film from GM about the clay-model process.

Olds Toronado mockup | Richard Earl

Stylists used special knives and rakes to smooth and sculpt the material, with the whole process sometimes taking as long as a year. To this day, even as digital technology , 3D printing and computer design tools like SolidWorks and AUTOCAD have revolutionized every other aspect of the manufacturing process, designers still prefer clay models as the most direct and simple way to turn their visions into reality. And that styling process all started with Harley Earl at GM's Art and Color Section, with other manufacturers following in his footsteps.

Remember, much of this work was done under the radar so GM could keep an advantage over their competition.

It's worth noting here that Harley Earl put down his ideas as artist's renditions, with dozens of signed, beautifully-rendered drawings that his contemporaries and many of his successors weren't even aware of.

The Buick Y-Job

Harley Earl in a Buick Y-Job | Wikimedia Commons

Earl was responsible for the industry's first-ever concept car, the Buick Y-Job, which rolled out in 1938. He had the funding, the engineering staff, and a locked office for this top-secret project that was hailed as the Car of the Future.

This roadster was a one-off that was designed to attract attention, but also to showcase ideas and technology that had a chance of making it to the market phase with production vehicles. The sleek Y-Job featured hidden headlights, power windows, an electric top that could be concealed under a hinged metal boot, a 320-cubic-inch, 141-horsepower Buick straight-eight engine, wraparound bumpers and 13-inch wheels for a lower, sleeker stance (the Y-Job was less than five feet tall at the top of the windshield). 1930s-style running boards were long gone, and its integrated, flowing lines were unlike anything on the road prior to that time.

It was built on a Buick Super chassis and ended up just short of 20 feet long, with aircraft-inspired finned brake drums, and brakes that were actuated by bladders at each wheel rather than brake cylinders.

Any fan of mid-century Buicks will quickly recognize some of the Y-Job's styling features, such as the waterfall grill that's still a Buick signature to this day. Earl took possession of the vehicle and used it for his own daily driver for years, helping to attract even more attention to this radical concept car.

Harley Earl's Young Army

As far back as 1930, Earl was looking far down the road at how design would mature and become legitimized as a part of the wider automotive engineering process. He knew there would be a need for young talent in the field, and did his best to recruit aspiring stylists into the game. He then prodded and encouraged and inspired his hand-picked young artists and designers to innovate and improve on their designs, changing the automotive world in the process.

From 1930 to 1968, Fisher Body and Earl ran a talent search, encouraging boys and teenagers to develop their own sketches and designs for vehicles. The response was overwhelming - in 1930 alone, there were more than 145,000 entries and over $50,000 in awards (roughly $734,000 today) was dispensed. By the early 1960s, the contest grew to rival the Boy Scouts in size, with aspiring designers turning out sketches, clay models and other iterations of their ideas.

This period also saw the genesis of the Detroit Institute of Automobile Styling, which actually advertised in the back pages of Popular Mechanics in the post-WWII years. In those days, you could take a correspondence course and have a legitimate shot at a job with GM's Art and Color Department. Hundreds of designers came up through the ranks this way.

GM's "Damsels of Design"

"I believe the future for qualified women automotive designers is virtually unlimited. In fact, I think that in three or four years women will be designing entire automobiles."

Another area where Harley Earl was far ahead of the game was the notion of diversity in the workplace. In fact, he put together the first all-female design team in mid-century American industry, and had the steadfast backing of GM's upper management every step of the way. Four of the designers were actually poached from GM subsidiary Frigidaire, where they had put in work on the Kitchen of Tomorrow concept.

Source | Richard Earl

The design team worked on interior elements such as upholstery, fabrics, headliner, carpeting, trim, door panels and other details, although the instrument panel was somehow off-limits. Some of their work made it to the show-car circuit, including things like a child-friendly backseat in an Olds wagon, complete with a magnetic game board, toy storage and other features.

Designer Ruth Glennie fielded the "Fancy Free Corvette" in 1958, with four sets of seat covers (one for each season). Their efforts incorporated things we now take for granted, such as storage cubbies, retractable seatbelts, lit vanity mirrors, childproof door handles, and more.

When Earl retired in 1958 and Bill Mitchell took the helm, the department was dispersed and several women went on to take other jobs at GM. One designer, Dagmar Arnold, went on to a job at IBM where she received the patent for the external design of the 1301 Disk Storage Unit.

Here's a GM film on this design team and their work.

The Motorama Show

In the 1950s, the possibilities for the future in America seemed limitless. New materials, new technology, vastly expanded manufacturing capacity, and postwar optimism made for an exciting time.

Jobs, money, consumer goods, and innovations were everywhere, and Americans were intoxicated by the ideas of nuclear power, space travel and jet aircraft. General Motors needed a great way to capture attention and market the latest from the company, and Harley Earl's Motorama Show was the perfect avenue for that.

From 1953 to 1961, the Motorama roadshow went to cities like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston and Dallas, showcasing Earl's dream cars and concept cars, and building mystique in the minds of consumers.

It's estimated that 10 million Americans attended the Motorama shows during these years, and some of the technology and innovations on display were remarkably forward-thinking. This 1956 Motorama film, for example, envisioned the far-off world of 1976 when families could take off on road trips in semi-autonomous cars, with traffic managed by district controllers (much like air traffic control) and each car would be equipped with its own onboard computer for navigation and communication.

The 50s Motorama films may seem like marvels of mid-century camp today, but they also point to a sky's-the-limit time in America when anything seemed possible. The Motorama roadshow was an ingenious way of selling imagination and potential as much as reality.

The Corvette

In the early 50s, Earl became interested in the European sports cars that were making headway on the racing circuit. He also noted that WWII GIs stationed in Europe had been impressed with sporty cars like the MG-TC and were importing them back to America, and tweaking them for performance.

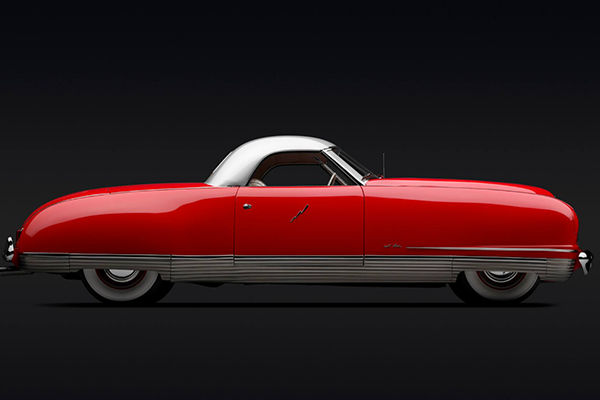

He saw a niche for an all-American sports car and launched "Project Opel" (not to be confused with the German GM brand) behind closed doors at the company. Inspired by the Jaguar XK-120 and the Cistalia 202 Nuvolari roadster, Earl began planning and sketching an all-new design.

Partnered with young designer Bob McLean, Earl was originally leaning toward steel as a body material for the new car. General Motors experimented with fiberglass-body cars for the Motorama circuit and had developed a fiberglass-body Chevrolet convertible prototype. When that convertible was rolled in an accident and came through more-or-less unscathed, it was time to consider the material more closely. The problem was that nobody at GM had experience in how to form and work with fiberglass, let alone mass-produce a fiberglass-body car.

It's become sort of an article of faith that the Corvette was the first plastic- or fiberglass-body car from General Motors, but other experimental models coincided with the rollout of the Corvette. In the early 50s, the Cadillac LeMans, Oldsmobile Starfire, Pontiac LaParisienne and Buick Wildcat all debuted on the show-car circuit with fiberglass or plastic in place of sheet metal. Low-slung and racy, those show cars were deemed "a progress report in plastic technology" by GM executive Charles Chayne. It was the Corvette, though, that made the cut and became the first car to make it from the Motorama circuit to general production, more or less unchanged.

Source | Richard Earl

In the spring of '52, a company called Naugatuck Chemical had designed a fiberglass-body sports car called the Alembic-1. Impressed, Earl and GM arranged to have the car delivered to the company for a month of evaluation. Earl was impressed by the light weight and the fact that tooling for the material would give the freedom to use the flowing, rounded, curved shapes he favored. They decided that the new sports car would have a fiberglass body.

After some debate as to which GM division should field the new car, Chevrolet's chief engineer noted that it would be the perfect vehicle to overhaul his brand's rather stodgy image. The new car's lines, wheelbase and dimensions were close to the Cistalia model and looked completely unlike anything in GM's lineup. Unfortunately, the only engine available for the car was the 30s-era Chevrolet "stovebolt six," a 235-cubic-inch flathead straight-six. It was modded with three Carter side-draft one-barrel carbs, higher compression and a fatter camshaft, eventually putting out 150 horsepower and 223 lb-ft of torque. Since there was no manual gearbox that could handle that sort of torque rating, it was mated to a Hydramatic automatic and floor shift.

Dubbed the XP-122, a prototype was put together for the Motorama shows, where it made an immediate impact. The new model was originally going to be named "Corvair," but, named after the small, maneuverable, fast patrol ships, the name "Corvette" stuck. Once production was green-lighted, an assembly line was set up in Flint and the company began producing Corvettes. Unfortunately, fiberglass bodies were harder to work with than steel and each car required considerable hand-sanding and shaping.

Only 300 Corvettes were produced and sold in 1953, and the six-banger engine and slushy two-speed automatic didn't do much for the car's performance reputation.

The new Corvette was also pricey—more than double the cost of a Chevrolet 150 coupe. Sales continued to languish through 1955, and it looked like the 'Vette was going to be a dead duck. Then came Chevrolet's 265 V8, the first ever overhead valve V8 from the company; that - along with the market threat from the newly-introduced Ford Thunderbird - meant that the Corvette was going to be a contender.

Harley Earl and the Tailfin

In 1948, the United States was the most prosperous country in the world and the victor of a bloody, devastating global war. Americans were optimistic and looking eagerly toward the future, and GM was in an especially good place going into the postwar years. The company was flush with cash from wartime contracts, while Ford was haemorrhaging money and losing executives right and left.

For Harley Earl and fellow designer Bill Hershey, nothing spoke of the future more than aircraft designs. Inspired by the lines of the WWII P-38 fighter and the graceful anatomy of fish and whales, Earl and his team drew up sketches and clay models for the '48 Cadillac that incorporated a raised ridge toward the back of the rear fenders, and the tailfin was born.

Photo courtesy Flickr

Before long, Chrysler, Ford and other GM divisions were all offering their own iterations of the tailfin, touted as "enhancing stability at high speeds." They reached an apex with the soaring fins of the '59 Cadillac and late-50s Chrysler models, but fins were also difficult to repair after a collision, and by the early 60s they were on the way out. The exception was Cadillac, which retained at least some form of fins through the early 90s. Still, Harley Earl's late-40s Caddy design ended up being the feature that defines the 1950s in pop culture, to this day.

Design Innovations

Here's just a partial list of some of the innovations that are part of the Harley Earl legacy, things we just take for granted on today's vehicles:

- Elimination of running boards

- Chrome body molding, window frames, trim

- Streamlined, flush fenders and bumpers

- Headlamps mounted in front fenders

- Steering wheel-mounted horn button

- Flush door handles

- Onboard computer (in concept cars)

- Onboard radar for collision avoidance (in concept cars)

- Yearly styling changes and "dynamic obsolescence"

- Distinct grilles and front fascia to differentiate makes and models

- Wider, lower bodies and lower center of gravity

- Heated seats

- Power windows

- Keyless entry

- Needle-type speedometer

- Integrated, comprehensive instrument panel

- Built-in car radio and speakers

- Contoured rear window and wraparound windshield

- Concealed gas filler cap

- Hidden spare tire

- Integral trunk and roof designs

- Interior sun visors

- Crash test dummies

- Built-in parking lights and turn signals

When Harley J. Earl retired from General Motors in 1959, he said, "You will never know what the industrial products of the future will be like, but the secret is to keep trying to find out.... I'd rather try crossing a river on a path of bobbing soap cakes than make predictions about the car of tomorrow. The footing would be far safer."

You may not know Harley Earl by name, and that's fine; that's how he would have wanted it. There's no getting around the fact, however, that his indelible mark on automotive design changed the business and American culture forever.