Fact or Internet myth? Read about one person's struggle with personalized license plates, plus brush up on your knowledge of these automotive necessities.

In 1979, or so the story goes, Robert Barbour of California decided to get personalized plates. The application asked him to list three choices, just in case a desired plate wasn’t available. So, Robert writes:

- SAILING

- BOATING

- NO PLATE

“SAILING” was already taken. “BOATING” was . . . already taken. So, even though Robert had meant that he had no third choice, the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) sent him plates that read–you guessed it–“NO PLATE.”

This wasn’t what Robert had in mind, but he had to admit that these plates were pretty distinctive, so he put them on his car. Four weeks later, he received a notice for an overdue parking fine; then, he began receiving them from all over the state–daily.

Ends up that, when a California police officer ticketed a car that had no plate, they wrote on the citation: No Plate. With the magic of technology, the DMV computers sent the citations to the gentleman whose plates matched the note on the tickets. Meaning, of course, to Robert.

In a matter of months, Robert received about 2,500 notices. When he contacted the DMV, they suggested that he get different plates. Instead, he responded to each citation with a letter explaining the situation; often that worked. Sometimes, though, he had to appear in front of a judge to explain further.

A couple of years later, the DMV requested that police officers write “None” rather than “No plate” when a cited vehicle had no license plate. This slowed down the number of notices Robert received to, oh, about five or six a month. That worked well for Robert and apparently nobody in California had personalized plates reading “NONE.”

A couple of years later, the DMV requested that police officers write “None” rather than “No plate” when a cited vehicle had no license plate. This slowed down the number of notices Robert received to, oh, about five or six a month. That worked well for Robert and apparently nobody in California had personalized plates reading “NONE.”

But. Always a but, isn’t there? Some officers wrote down “Missing” to cite vehicles without plates–which caused the avalanche to go to Andrew Burg who (c’mon, you already know the punch line) had personalized plates that read “MISSING.”

By now, you’re assuming that this is one of those Internet tales that grows larger with each telling, much like Pinocchio’s nose. But, according to Snopes, this–and other personalized plate disasters–actually happened.

License plate laws

Although Robert Barbour’s story shows how laws can cause problems for innocent people, these laws exist to keep order–and it just makes good sense to follow them. Otherwise, you can be fined. According to LegalMatch.com, here are the main requirements to stay in compliance; each plate must be:

Although Robert Barbour’s story shows how laws can cause problems for innocent people, these laws exist to keep order–and it just makes good sense to follow them. Otherwise, you can be fined. According to LegalMatch.com, here are the main requirements to stay in compliance; each plate must be:

- Currently valid

- Clearly visible:

- Mounted in the proper place without obstruction

- Cleaned so that it is free of debris, mud or dirt

- Without a protective plastic cover if your state has banned them (because of the glare)

More than half of the states in the United States do NOT require front license plates. To get more information about your state’s requirements, you can use this page from the Department of Motor Vehicles.

History of license plates

Hard as it is to imagine today, throughout most of history, people didn’t need to have license plates. Before there were cars, no one apparently saw a need for identifying vehicles, such as horse-drawn buggies, with numbers. And so, when cars were brand new, there was no already-established system for license plates that could be transferred from one type of vehicle–the buggy–to the next: cars. Officials quickly began to realize the importance of being able to identify cars, though, because a form of a license plate was apparently used as early as 1896 in the German state of Baden.

Hard as it is to imagine today, throughout most of history, people didn’t need to have license plates. Before there were cars, no one apparently saw a need for identifying vehicles, such as horse-drawn buggies, with numbers. And so, when cars were brand new, there was no already-established system for license plates that could be transferred from one type of vehicle–the buggy–to the next: cars. Officials quickly began to realize the importance of being able to identify cars, though, because a form of a license plate was apparently used as early as 1896 in the German state of Baden.

As far as the United States goes, New York started requiring license plates in 1901, but didn’t issue them. In other words, each individual owner was responsible for creating his own plate, using his initials as the identifying mark. (Can you imagine how many duplicate license plates would exist today if this system were used?)

“New York then began assigning numbers,” says Jeff Minard, license plate historian for the Automobile License Plate Collectors Association (ALPCA). “That system worked for years and people created plates out of leather or painted the number on their vehicle–or used house numbers. Whatever worked. You could use whatever materials you wanted and whatever color you liked. As long as you paid a small fee and put the correct number on your car, you were good to go.” Other options included going to the local blacksmith to buy a metal plate; still other people had wooden plates.

Also in 1901, the city of Cleveland, Ohio required motorists to register with city officials and receive a license number. The owners apparently created their own tags here, too, putting the appropriate number on them; these tags did not need to have the word “Cleveland” on them. Toledo, Ohio also had a similar system.

In 1903, Massachusetts began officially issuing license plates (rather than assigning a number to a car owner and requiring him to create the plate). The first one issued simply contained the number “1” and was given to Frederick Tudor. And, in multiple places online, it states that one of his relatives still has an active registration for this plate.

So, we asked Jeff if this was true and he confirmed it as fact. “Tudor was the head of the highway department in 1903,” Jeff says, “and so he was able to secure that number. And, in Massachusetts, license plate numbers can be inherited. That’s also true in Washington, Rhode Island, Delaware and Illinois.”

We dug around for more info and found an article on the subject by Ryan Lee Price on the Chilton DIY website. In June 1903, Ryan says, Massachusetts wanted to solve a dual problem: to generate revenue so that they could improve the road systems and to identify drivers and cars involved in breaking traffic laws. So, the newly created “automobile department” required all drivers to register their cars and pay an annual fee of two dollars; drivers were given until September to fulfill the requirements. By December 31, 1903, 3,241 cars and 502 motorcycles were registered, which raised $17,684–and those drivers typically wanted to obtain the lowest numbered plates possible “as a symbol of status.”

As for Frederick Tudor, Ryan provides these facts:

• He received his license plate on September 1, 1903

• He lived in Brookline, Massachusetts

• Tudor was also the nephew of Henry Lee Higginson

Although Higginson is not especially well known today, he was a Civil War veteran, a respected businessman–and the founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1881. So, in other words, he had some clout.

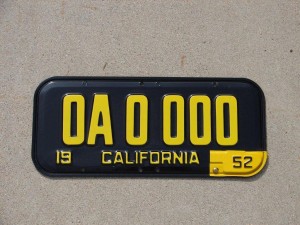

Early Massachusetts plates were iron, covered with porcelain. The background was cobalt blue and the number was in white, along with “MASS. AUTOMOBILE REGISTER.” When the plates contained single digits, they were quite small. As the registration numbers got larger, so did the size of the plates, which suggests that state officials didn’t foresee the state housing large numbers of drivers.

These old license plates weren’t dated, according to Jeff (and here is a look at some of those early plates). “Some states made you pay money every year, but you kept the same plate. Some time around World War I, though, state officials began saying that the current systems of issuing license plates was chaotic and that’s when the appearance of license plates became more standardized within a state. By 1918, according to the Smithsonian Institute, all states required them.

During the early days, drivers in some locales were required to have both a city and a state plate. In Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii and New Mexico, license plates were required before they were even states. Because of all the variations in laws, plates can be classified as pre-territorial, territorial, pre-state and state.

Trivia: vintage license plates

The ALPCA site lists fun trivia, much of which comes from License Plates of the United States: A Pictorial History, 1903 to the Present by Jim Fox. For example, did you know that the 1916 California plate has a spot where the owner needed to scratch in his name? Or that, during World War II, some states made their plates out of a soybean-based fiberboard? And, yes. The goats did find them to be tasty.

But, for the curious-minded, it’s this mystery that sticks in the mind: from 1910 to 1913, in Kentucky, plates first contained a small letter “B,” which was then replaced by an “L,” then an “M” and then a “G.” And, of course, nobody knows why! Argh.

License plate collectors

“This hobby attracts people from all walks of life, from farmers to senators, from undertakers to entertainers.” (License Plates of the United States: A Pictorial History 1903 to the Present by James K. Fox)

When asked why he chose to collect license plates, Jeff Minard says, “Some people collect. Other people don’t. Some collect stamps and coins, or spoons or ashtrays. I liked how plates could come off of a car and then be hung in a garage, and I kept those.”

And, it simply went from there. “There are very few books about this type of collecting,” he continues, “and little knowledge about the plates. That can be a turnoff for some people, while other people like that. License plates also used to be difficult to find, but that was before eBay.” (Note: at the time of writing this post, after typing “license plates” into the eBay internal search bar, there were an astonishing 505,858 results!)

Jeff brings up an interesting point–that there is no central archival place to gather information about license plates. “Each state has its own DMV,” he says, “and if you call, someone there can tell you about the current plates, but not about historical information. In a sense, the amateur collectors are really also the historians.”

ALPCA has existed as a club for collectors for more than 60 years. Currently, according to Jeff, the club has 3,500 members; altogether, there have been more than 11,000 in the club’s existence. There are also about 1,000 people in a European club and 1,000 in an Australian club. “Plus,” he adds, “there is the guy on the street who has ten old license plates hanging in his garage, just because. Maybe because he just hasn’t thrown them away. I’ll bet that millions of men in the United States do that.”

Personalization of the plates adds a level of interest. One way to do that is to pay extra and be able to choose how your plates read (as Robert Barbour did in 1991). Another way is to choose a specialized kind of plate, an affinity plate, that “feeds into personal interests,” whether that means saving the whales, neutering pets, visiting national parks or something else entirely. “Tennessee has about 200 choices,” Jeff says, “while California has five.”

Why the difference? “California has too many cars and too much administration to be able to offer numerous choices,” Jeff explains. “But, the eastern and southern states typically have plenty of options, which makes collecting them fun. Some people will buy more than one license plate in a year and switch them out, almost like changing shoes. What you don’t want for your personal collection can be sold on eBay or at swap meets or on other websites.”

As if those weren’t enough reasons to collect, Jeff adds this: “License plates are quirky. They hang on the walls of bars, coffee shops and country restaurants. It’s just a cool thing to collect. If you haven’t traveled somewhere but would like to, you can get the license plate. You can even collect plates from around the world: from Vietnam, from Cambodia, from the Philippines. For $15 to $20, you can have the world at your fingertips.”

A look at a niche collection of vintage license plates

As Jeff mentions, different collectors have different interests–and we at Advance Auto Parts talked to a man, Charley Kulchar, who focused his collection on Ohio license plates. He started his collection “long ago” and what fascinated him enough to start his collection were the first four years of state plates in Ohio, before they became painted metal.

“In 1908 and 1909,” Charley says, “they were blue porcelain with white letters and there was a zero with an H in the center to designate Ohio.” In 1910, state officials experimented with using red porcelain “with black brushed through for a woodgrain effect”; and, in 1911, they tried white porcelain with black lettering. Switching to flat metal plates with painted lettering in 1912, letters became embossed in 1918.

After that, the state of war and peace dictated significant changes in Ohio’s plates. “Ohio license plates were issued in pairs until 1943,” Charley says. “But, because of the steel shortage during World War II, people didn’t receive new plates in 1943. Instead, they got a sticker for their windshields.” In 1944 through 1946, the steel supply apparently freed up enough for Ohio officials to issue single metal plates, returning to pairs from 1947 through 1951–when the Korean War caused more changes: a sticker in 1952 and a single plate in 1953.

During the single-plate years, some cities, including Cleveland and LaGrange, offered what was called a “booster plate” for the front of the car, the forerunner of today’s personalized plates. “It was just an accessory, a novelty,” Charley explains, “often seen with folks’ initials on them.”

Charley says that he continued to collect Ohio plates (all double-plate years, with embossing gone after 1973) until 1975, when people no longer needed to buy new plates each year. Instead, a sticker could be purchased and placed on the bottom right hand corner of the back plate to indicate current registration.

And, remember how Cleveland was the first city to require registration of cars in 1901? Charley says that “registration was required if you lived in the city or if you spent 24 hours in a row in Cleveland, so people who did business in the city often had to register, too. They were each given house numbers to use.”

Charley has spent considerable time studying the handwritten registration ledgers from 1908, when Ohio first required plates. “You needed to list your name, the type of auto you had, its horsepower, its serial number and where you lived. You were then assigned a number, starting with 1. Of course, the influential people–usually those in mining, steel or some other industry–got the low numbers with Francis Prentiss, owner of the Cleveland Twist Drill Company, getting both #2 and #4.”

It’s hard to locate single-digit plates, since there were only 9–and not all that easy to find double-digit ones, either, since there are only 90 of them. So, Charley has focused on finding triple-digit plates. “In 1930, when the Cleveland Municipal Stadium was being built,” he says, “it was placed over the city dump. Then, when it was torn down in 1996, a number of 1911 porcelain license plates were found and circulated. Many were quite deteriorated but, since they were made of porcelain, they are still legible.”

Charley owns “a couple of thousand plates,” explaining that, sometimes, he might “only want one or two plates, but needed to buy an entire collection to get them. Then, I’d trade, sell or scrap others of the plates.” His collection grew to the point that he had a plate from the entire timeline of 1908 to 1974. In recent years, he says, the hobby has changed because of the Internet. “You used to go to swap meets to buy and sell and you got to meet a lot of nice people from around the country. Now, you can just put up a plate on the Internet–or buy one that way. It’s a better way to sell but less personal, and nowadays you can become an overnight collector just by buying online.”

Editor's note: How about you? Are any of our readers collecting old license plates? What are your thoughts? Please share in the comment below!