Motor oil is the quiet optimizer that keeps our cars running smoothly and for a long time. Its main function is to lubricate the various moving parts in an engine so that they not only run more smoothly in all types of weather but also last longer. After all, an unlubricated set of pistons, crankshafts, and other active components leads to the kind of friction that destroys engines quickly.

In the history of motor oil, many people—and companies—contributed innovations to engine lubrication. In some cases, it was teams, but we've narrowed down our list to four individuals, without whom motor oil as we use it today would not have been possible.

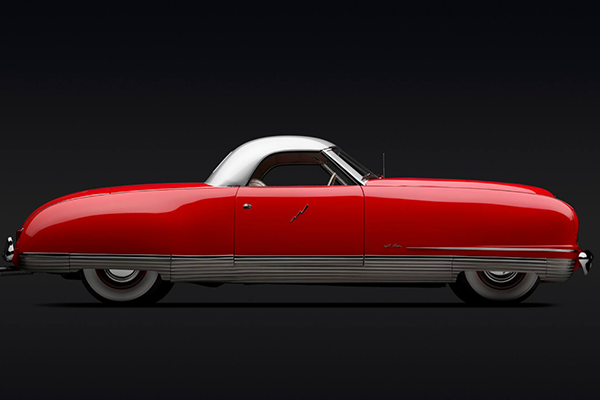

Source | Valvoline

Dr. John Ellis

Not too long after petroleum was discovered in western Pennsylvania in 1859, Michigan physician Dr. John Ellis began research on the oil's medicinal properties. Though he never found much in the way of health benefits or curing powers, Ellis did see its potential as a lubricating agent for the cylinders in railroad steam engines and other industrial machinery, which were increasing in number thanks to the buildup of railways and the burgeoning industrial revolution.

Up until then, these machines were generally lubricated by animal and vegetable oils, which were abundant and viscous, but not always kind to the engines or flexible with certain temperatures. Petroleum or mineral-based oil, on the other hand, was more stable at different temperatures but lost its lubrication qualities when mixed with water. Ellis discovered that adding a small amount of tallow found in animal oils helped preserve the lubrication of mineral-based oil. And thus the first compounded engine oil was born.

Sniffing out a business opportunity, Ellis relocated in 1866 to Binghamton, New York, which at the time was a reasonably sized and affordable crossroads of the railroad and manufacturing industries. That same year, he founded the Continuous Oil Refining Company, where he produced the new compounded steam engine oil using a patented steam boiler.

Increasingly used in the various steam engines and industrial machinery, Ellis' oil—soon to be named Valvoline after the valves it was lubricating—helped his company flourish. Eventually, the company relocated to Brooklyn, then across the Hudson River to Shadyside/Edgewater, NJ, and, by the turn of the century, had created other compounded oil combinations, including a type of motor oil for internal combustion engines in race cars.

In 1895, Valvoline lubricated the two-cylinder 1-3/4 horsepower Duryea wagon that won the first auto race in America. In 1904, Henry Ford broke the land speed record—at 91.37 mph—in the four-wheel “999," which had a gasoline engine that was lubricated and optimized by Valvoline motor oil. Four years later, the auto magnate publicly endorsed the Valvoline brand when he launched the world's first mass-produced, affordable car, the Model T. That car's popularity also helped make Valvoline a household name, and the basic compounded oil recipe that Ellis originally discovered is the same basic oil that we use in cars today.

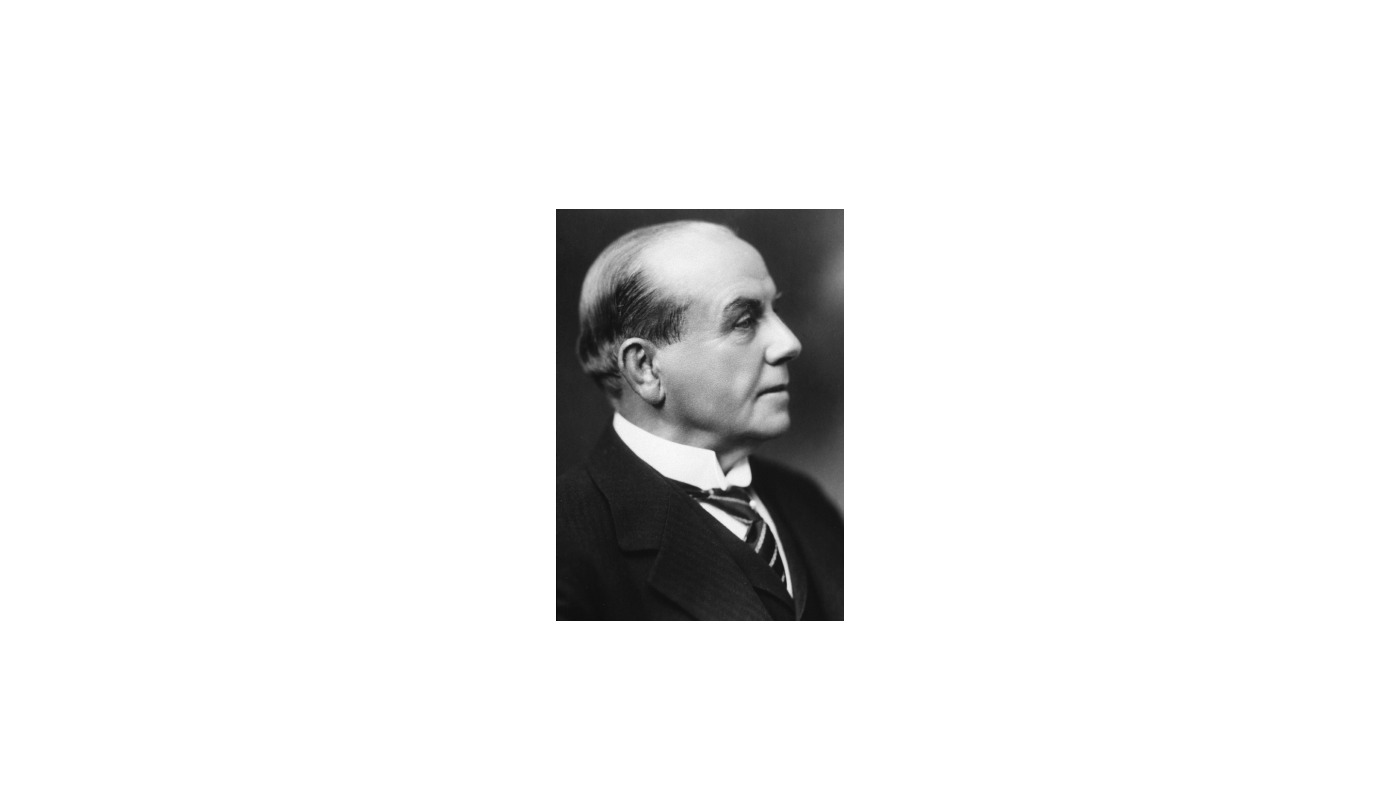

Source | Castrol

Charles Wakefield

In 1899, before cars, motorcycles, and planes changed the world, English entrepreneur Charles Wakefield founded industrial lubricant company CC Wakefield, which was eventually renamed Castrol, after the castor oil that Wakefield's team mixed with petroleum. Like Ellis, Wakefield discovered that adding a small amount of vegetable oil made a truly effective and versatile lubricant for engines.

Not long after he founded the company, Wakefield worked as a public servant, eventually becoming the mayor of London. As a result, he was knighted and eventually rose to the title of Lord Wakefield. But he never stopped working. In fact, one of his greatest innovations was the drip feed, or automatic, lubricator, which he patented in 1918. This ensured lubrication flowed consistently, and in all types of weather, to specific, hard-to-reach parts of the engine, an essential task since lack of lubrication makes for an eventually damaged engine.

Wakefield was a philanthropist, whose gifts included everything from scholarships for the Royal Air Force College to car and seaplane race prize money.

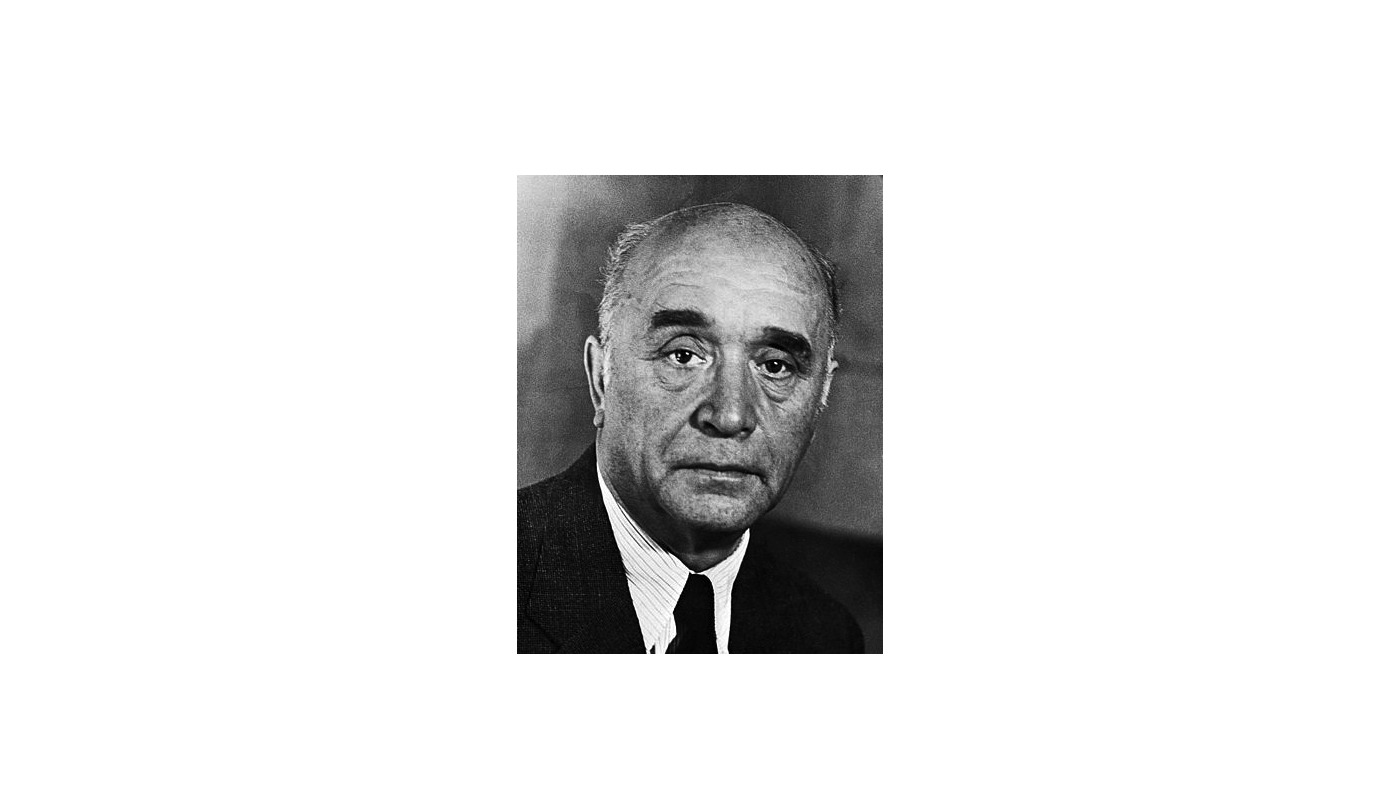

Source | B. Schmitz-Sieg/Wellcome Library, London

Friedrich Bergius

The origin of synthetic oil, motor or otherwise, is often up for debate, if only because so many people and teams were involved in its overall development. But if we are to come up with a synthetic-motor-oil-history "first," it would have to be Friedrich Bergius, who in 1912 and 1913 developed and patented a process by which brown coal is hydrogenated under high pressure to produce the liquid hydrocarbons that make up synthetic fuel.

But here's where it gets complicated. Economic turmoil and inflation in post-WWI Germany led Bergius to sell his patent to German chemical company BASF. There, he joined chemist Carl Bosch to further develop and commercialize the process, and, in 1931, the pair were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their work on these high-pressure techniques.

Innovations around synthetic oil were taking place simultaneously in the United States—namely by Standard Oil and Union Carbide—but the production and commercialization was given momentum, sadly, by the German WWII apparatus, when almost 10 percent of Hitler's war machinery ran on synthetic fuels. Not surprisingly, Bergius was unable to get work in Germany after the war, and he ended up in Argentina, where he died in Buenos Aires in 1949. The Bergius process may not be used in synthetic motor oil production today, but it was responsible for the very concept of synthetic oil, which other innovators would eventually bring to market for everyday cars.

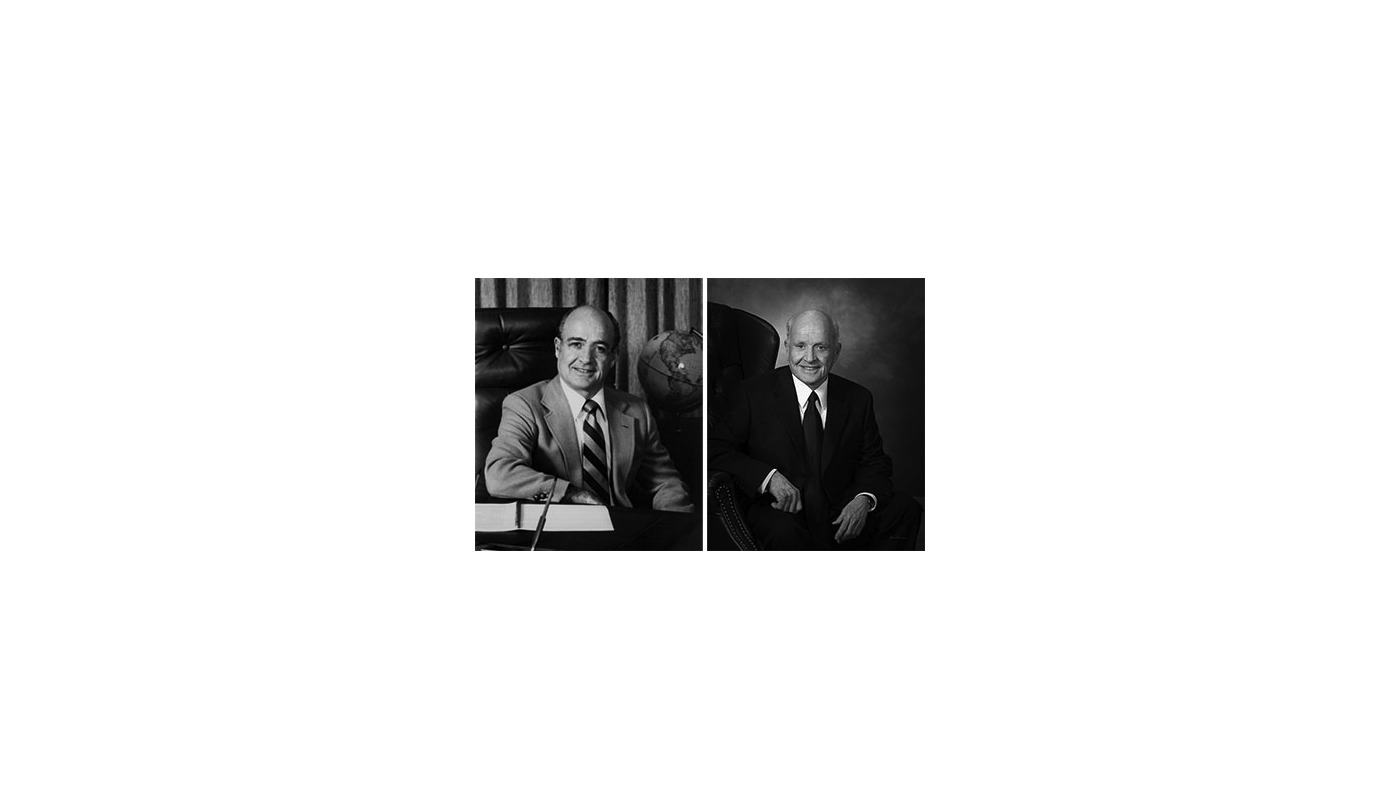

Source | Amsoil

Albert J. Amatuzio

It wasn't until nearly 20 years after the end of the second World War that synthetic motor oil got its next major push. An Air Force and Air National Guard pilot, Minnesota native Albert J. Amatuzio, who died in April 2017, knew the superior qualities of synthetic oil as applied to jet engines, and figured its benefits could apply in a mass-market context to motor vehicles, too.

In the 1960s, Amatuzio began work on developing synthetic oils, formulating his first by 1966. It wasn't until 1972, however, that 10W-40, the first synthetic motor oil that passed muster with the American Petroleum Institute, hit the market (produced and sold by Amatuzio's company, Amsoil, which he founded the same year). At last, the benefits of synthetic motor oil—higher viscosity, better cold weather performance, and increased horsepower and torque—had use for everyday drivers (though it would take years for the prices to come down).

Source | Heisenberg Media/Flickr

Future Forefixers: Elon Musk

Elon Musk doesn't necessarily have anything to do with motor oil itself, but his passion and push to develop the electric car may well usher in an oil-free future. That's because electric cars don't use internal combustion engines—no pistons, crankshafts, or rods—only rotors, which means that besides not using gasoline, they don't need motor oil. And, sure, Musk isn't the only electric car evangelist and entrepreneur—these types have been around since the early 20th century—but given that he built Tesla out of nothing, well outside of the Detroit system, and that it's now more valuable than Ford or GM, is just one indication of the bullish future for EVs.

It's no surprise that other car manufacturers are stepping up their development in this area, with countries such as the UK, France, and Norway pledging to ban all-gasoline cars by the middle of this century, and manufacturers such as Volvo announcing that they'll stop producing all-gasoline cars after 2019. For better or worse, motor oil may become a thing of the past by the end of this century.